To offset the loss of educated workers to “superstar cities,” more places are offering perks like relocation stipends and the option to work remotely.

It was the spring of 2010 and Erik Johnson had just graduated from the University of Vermont with a bachelor’s in economics. Two years prior, Johnson had moved to Burlington from Boston to finish his degree, attracted by the Green Mountain State’s natural beauty and laid-back culture. Vermont had a lot of perks for an avid trail runner like Johnson, but he quickly learned that job opportunities were not among them. After a nearly year-long search, Johnson was grateful to land a gig as a web developer at a local company. It didn’t pay much, but it was better than nothing. Still, he concluded that Vermont’s largest city (population 42,000) didn’t offer much in the way of career advancement. So, when Johnson was offered a job at a research university in Boston the following year, he jumped at the opportunity.

Johnson’s story is hardly unusual. For decades, young, highly educated Vermonters have left the state to pursue career opportunities in bigger cities. At the same time, Vermont has failed to attract and retain enough outside talent to offset this loss. This phenomenon is known as “brain drain,” and there’s an emerging consensus among policymakers that it may contribute to many of America’s social, economic, and political problems.

In April, the Congressional Joint Economic Committee found that highly educated adults in their thirties were fleeing rural and postindustrial states to major tech centers like San Francisco, New York, Seattle, and Boston. The report, based on 40 years of Census data, said states in the southeast, New England, and the Rust Belt were losing the most talent to these “winner-take-all” cities. Vermont was one of the hardest-hit states.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution say this brain drain fuels “entrenched poverty, deaths of despair, and deepening small-town resentment” of coastal elites. “Overconcentration in the largest metro areas and this evacuation everywhere else is a serious problem,” says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at Brookings. But the widening economic gap between the so-called “superstar cities” and the rest of the country is a relatively new phenomenon.

America’s ‘Great Divergence’

Between 1940 and 1980, the wage gap between poorer cities and richer cities in the US actually shrank, according to research by Penn State economist Elisa Giannone. Since 1980, though, Giannone found that college-educated adults increasingly moved to cities that already had large populations of high-skilled workers. Even so, the demand for workers versed in new digital technologies outpaced the supply, pushing wages up in these cities and attracting even more skilled workers.

This has led to what UC Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti calls “America’s great divergence”: A handful of cities attract the bulk of high-paying jobs, increasing the economic disparity between those who work in these cities and those who do not. Moretti says the trend is the result of what economists call “agglomeration benefits.” When a bunch of skilled workers and firms in a similar industry are located near one another, it’s easier to find specialists, knowledge tends to spill over from one firm to another, and firms see higher rates of innovation and productivity. The result, Moretti says, is that “successful cities generate more success” by attracting still more firms and workers looking to capitalize on these agglomeration benefits. It also explains why firms and workers in highly specialized industries are reluctant to set up shop elsewhere—no one wants to be the first to go to an area that lacks these benefits.

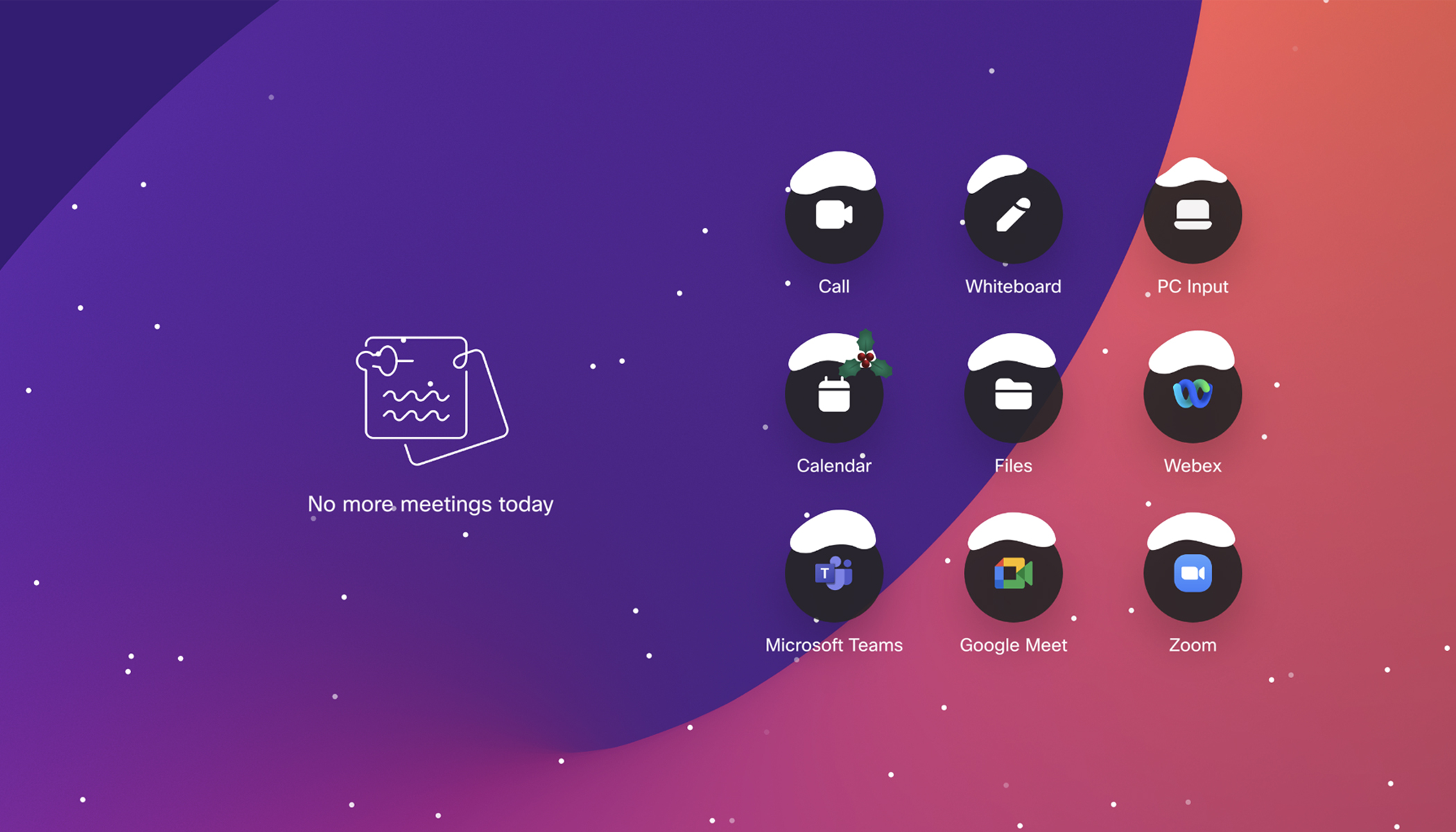

In an effort to reverse this trend, policymakers in Vermont and elsewhere are betting on programs that tap digital technologies to entice skilled workers to relocate. Last year, Vermont governor Phil Scott signed into law a measure designed to attract full-time remote workers to the Green Mountain State.

The Remote Workers Grant reimburses employees up to $10,000 for relocation costs, office equipment, and other expenses, as well as in-kind perks like a membership to a coworking space. State senator Virginia Lyons, the bill’s sponsor, says she wanted to attract young tech workers to Vermont to bolster the state’s tax base and rejuvenate its cities.

The first round of applications opened in January and attracted 33 remote workers from a variety of industries including software, insurance, and media. Amelia Potasznik-Kriv, an immigration attorney, moved with her wife and two children from Dallas to Burlington in January. She says the nature of her work, which involves digitally communicating with people around the world, plus a long and amicable professional relationship with her boss, made the transition to a more rural setting seamless. “I have friends who warned me that it would feel too small coming from a big city like Dallas, but it feels perfect,” Potasznik-Kriv says. “It has all the great things about big city living—art, music, festivals—but it feels much more human-scaled.”

Some private groups are working to establish similar remote work programs elsewhere. Last year, the George Kaiser Family Foundation began offering remote workers $10,000 in relocation and living expenses to move to Tulsa, Oklahoma. Ten thousand people applied over 10 weeks and the organization selected 100, using input from the community and a rigorous interview process.

Among those selected was Dennis Howell, a 34-year-old technical operations analyst who moved to Tulsa from Los Angeles with his girlfriend. Howell says he had no problem convincing his employer to let him go remote and now splits his time working from home and one of the coworking spaces provided as part of the program. Although Howell had never been to Tulsa when he applied, he says the experience of living in the “smaller but growing city” has been positive. Howell says he especially likes the quiet environment and people he’s met, and plans to stay in Oklahoma after his year with the remote work program ends.

It’s Hard to Copy Silicon Valley

Efforts by cities and states to create clusters of specialized workers are not without precedent, but Moretti says that historically almost none of these efforts to create the “next Silicon Valley” have succeeded. Although there are exceptions—Moretti cited Austin and Raleigh-Durham as cities that have deliberately created dynamic, high tech local economies—the odds are against these types of initiatives.

Consider the push in Appalachia to teach laid-off coal miners to code. In 2017, the Appalachian Regional Commission granted $1.5 million to Mined Minds and other nonprofits pushing coding in the region in an effort to strengthen workforce skills. However, a recent New York Times report found that almost none of the coal miners who enrolled in Mined Minds landed programming jobs. Many miners learned to code, but transforming the economy of an entire region turned out to be harder than teaching JavaScript.

That’s a reality that Matt Dunne, a former Googler who worked remotely in Vermont, knows acutely. In 2016, Dunne founded the nonprofit Center on Rural Innovation, which last year launched the Rural Innovation Initiative to create a network of “hubs” that provide a workplace for remote employees and help train locals in digital skills. Dunne believes his initiative can succeed where other programs have failed by creating a national network where workers trained through the program can connect with one another, and allowing employers to tap into a readymade pool of skilled tech workers.

The goal, in effect, is to use the internet to create agglomeration benefits that aren’t tied to a particular location. Dunne’s program also places a premium on entrepreneurship. This can overcome the reluctance of specialized workers or firms to be the first to move to an area. As Moretti notes, clusters of skilled workers tend to emerge organically around a successful seed firm. Dunne hopes to produce entrepreneurs whose businesses act as the seeds to attract more skilled workers to the area.

These programs are still in their infancy and it’s too early to say whether they’ll be able to reverse brain drain. Dunne has nine communities in the Rural Innovation Initiative network and plans to open a pilot coworking space in Springfield, Vermont, in August. Meanwhile, Vermont is doubling down on its commitment to attract more remote workers to the state. The second round of applications for the program opened in July and so far the state’s Department of Economic Development has approved 56 new remote work applications. Tulsa will open a second round of applications for its remote worker program this fall.

Despite the progress at these local efforts, Muro says a comprehensive federal policy, rather than local “experiments,” will ultimately be needed to reverse brain drain. He favors creating regional “growth poles,” mid-sized cities where the federal government would invest to foster research and development, much as Silicon Valley benefited from large infusions of government funding in the 1950s and 60s. Muro suggests focusing on 10 or so mid-sized metro areas, saying the benefits would extend to smaller communities nearby. He hopes that establishing these growth poles would, in turn, attract large companies to the area and foster local talent.

How Employers Feel

Some companies are embracing remote work without government help. Software development platform GitLab staked its company identity on remote work, hoping to take advantage of employee flexibility, increased productivity, and lower operating costs. With the soaring costs of housing and office space in San Francisco and other major tech hubs, larger employers are also encouraging remote work to save on salaries and rent.

In April, Twitter and Square CEO Jack Dorsey mused about the decentralized workplace of the future, saying “our center of gravity shouldn’t be San Francisco: we should be able to work from anywhere and contribute from anywhere and this concept of headquarters to me is a very old concept that is going to go away.”

Not everyone is so enthused about letting employees work from home. In 2013, Yahoo CEO Marissa Meyer infamously ended the company’s work-at-home policy. She justified the decision by saying that “people are more collaborative, more inventive when people come together.” Since then, several other major tech companies like IBM, Honeywell, and Reddit followed suit.

The irony of America’s tech-fueled brain drain is that the internet should have freed us from location-based employment and helped disperse high-skilled tech workers. In her 1997 book The Death of Distance, British economist Frances Cairncross heralded the ways that digital technologies, particularly the internet and mobile phones, were “killing location” and “loosening the grip of geography.” For Cairncross, one of the many implications of ubiquitous internet access was that “companies will have more freedom to locate a service where their key staff want to live, rather than near its market” and employees “will gain more freedom to live far from their employers.” Reality proved far messier.

Cairncross says she “misjudged” the extent to which concentrated labor markets matter in the knowledge economy, because they provide an available pool of specialized skills and other agglomeration benefits. So rather than decentralizing the American labor pool, the rise of the internet and digital technologies had the opposite effect: It accelerated its concentration. The face of this change is the San Francisco Bay Area, which consistently ranks as one of the most congested and expensive regions in the US. But a similar scenario is playing out in Denver, Boston, Seattle, and other major tech-driven metro areas.

Despite the agglomeration benefits for firms that concentrate in these cities, economists are in wide agreement that the trend is bad for the country as a whole. The areas left behind by skilled workers in search of greener pastures are experiencing a surge in deaths of despair like suicide and opioid addiction. The cultural and economic divide between the so-called “superstar cities” and the rest of the US is fueling a polarized political landscape that gives rise to candidates like Donald Trump.

Melvin Kranzberg, a former professor of the history of technology at Georgia Tech, once famously proclaimed that “technology is neither good nor bad—nor is it neutral.” Rather, Kranzberg realized that the effects of a technology must be considered in context, and can be good and bad at the same time. It’s an adage worth keeping in mind when considering brain drain in America. It is a mounting crisis precipitated by the internet and digital technologies, but these very same tools may also be our best hope for a solution.